Curating on the Frontlines: KB24 Preview with Waheeda Baloch

- The Aleph Review

- Oct 15, 2024

- 10 min read

Updated: Oct 16, 2024

Maliha Noorani

In advance of the Karachi Biennale 2024 Rizq|Risk, Maliha Noorani sat down in conversation with KB24 curator Waheeda Baloch. Head here to read the introductory curatorial note.

About the Curator: Waheeda Baloch, born in Mirpur Khas, the home of a generation of talented artists, has been linked to literary circles through her family. Waheeda’s curatorial practice is enriched by her experiences as an art educator and performance artist.

She holds a Master’s Degree in Curation from Stockholm University, Sweden, which she pursued after an MFA from Sindh University. Currently, she is working as a Professor at the Institute of Art and Design, Sindh University is enrolled as a PhD candidate at the University of Bonn, Germany.

Waheeda Baloch is the founder and curator of Art Fest, which is held at Sambara Gallery, Karachi. The framework for this annual exhibition, which has created a space for dialogue, both artistic and discursive, among Pakistani artists, was conceptualized by her for this non-profit gallery. She also has other national and international shows to her credit.

Maliha Noorani: How did you get involved in the forthcoming coming Karachi Biennale 2024?

Waheeda Baloch: I have always been very interested in public art. After I came back to Pakistan from my MA in Curatorial Studies from Stockholm, I really had this kind of mindset: why we don’t have public institutions for contemporary art in Pakistan?

When I founded Sambara Art Gallery in collaboration with the Culture Department of Sindh, it was at the Liaquat Memorial Library in Karachi. It was really nice to see the public response to the artworks. So, this Bienniale is actually an opportunity for me as a curator to reach out to that public.

MN: What demographic are you referencing to as ‘that public’?

WB: I mean the public at large: rural, urban, old, young, rich, low-income. I have previously worked with children in villages, so I am engaging those communities as well with the artists who are coming for KB24.

Earlier this year Anna Kunik, for example, came for a research project specifically for KB24. She’s an artist whom I met in Stockholm in 2011 when she was making her film on immigrants in Sweden. She expressed an interest in coming to Pakistan and since then we have shown her film (Silence Heard Loud) at the Sambara Gallery. I am excited for you to see what she is producing for KB24.

MN: It’d be great to understand more fully your context and background. Could you tell me a bit about yourself? I’m keen to to know more about your own practice and interests.

WB: I was born and raised in Mirpur Khas, Sindh and grew up surrounded by books and conversations on art and literature. My brother was a professor of Urdu linguistics and literature and we would often host a variety of artists, writers and other intellectuals. Being in the thick of such conversations shaped a lot of my interests—by the tenth grade I had already read all of Tagore! I also became quite interested in Russian literature. Despite this, I wanted to become an engineer, however, the artistic seed took hold and I ended up pursuing Fine Arts.

Eventually, I ended up at Jamshoro University (where I am now). My practice changed when I enrolled in the Art History department at Stockholm University; it was a new programme on art curation with a focus on law and management. I was the only Asian there. This is where I met Anna Kunik, who will be a part of our upcoming programme.

MN: Could you speak a bit about your curatorial practice? It’d be great if you could reference the works you think were landmark projects in your career, not in terms of scale necessarily, but certainly impact.

WB: I think that it was my first exhibition, Items of Dual Use (2012), which was a group show with two Swedish artists (Lina Persson and Henrik Andersson) and two Pakistani artists (Ayesha Jatoi and Muzzumil Raheel). This was a different experience for me, as the show consisted of four distinct projects, and also due to the theme itself. It was a way of looking at the private and public world, and their interlinkages.

This was a very ambitious project for me to get all these artists to work on this idea of duality. For example, Ayesha Jatoi’s installation (Clothesline) had a fighter jet with laundry hung on it. I was also focused on imagery and how images work as weapons—Lina Persson’s calligrams became a critique of how the western media misuses their freedom of expression.

I did not want art to be very difficult to understand for people. People make art and art is made for people. It’s not like we make art for aliens! Connection is important.

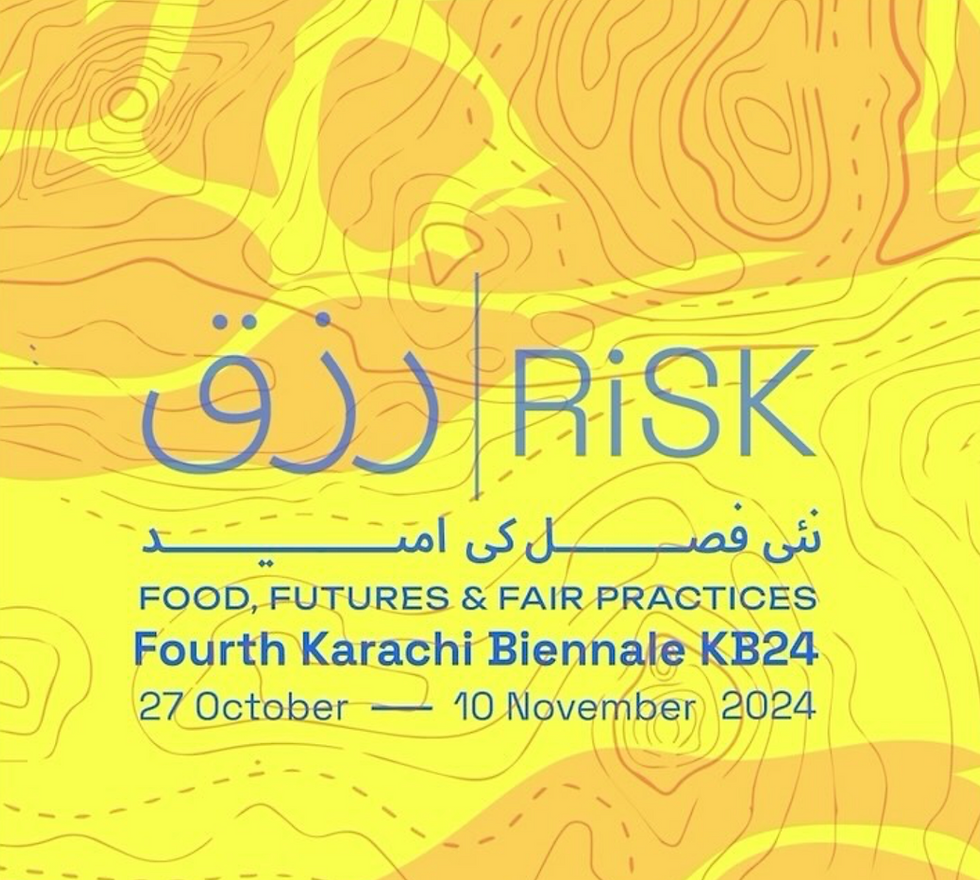

MN: Let’s talk about the title of this year’s Biennale: Rizq|Risk. The double-entendre is on the English word ‘Risk’ and the Urdu word ‘Rizq’. The wordplay is very clever and it pulls on both languages and opens up multiple meanings collectively. Could you expand on your vision and ambitions for KB24 with regard to programming and artists?

WB: It was a lot of hard work, actually, because it needed a lot of research on who is doing what and how we can connect it to our own society. And if I’m looking the global, how that can become local. So that was my idea. I did not want art to be very difficult to understand for people. People make art and art is made for people. It’s not like we make art for aliens! Connection is important.

I started with a lot of research about food security. I decided that we should not call it food insecurity, because the concept of food security already has the concept of insecurity in it.

MN: What is food security and what does it mean exactly to you?

WB: Food security is the lack of food—but it’s not exactly just the lack of food. It’s also about livelihoods in a larger sense. ‘Rizq’ then becomes more than just about food, but livelihood and concepts of abundance.

MN: Yes, ‘Rizq’ is not just food, the word denotes many other forms of abundance…

WB: Exactly, and actually ‘Rizq’ is a globally used term. Because when I was talking to Turkish and Moroccan artists, even when I was talking to regional artists, such as the Iranians—everybody understood the word ‘Rizq’ and everybody has certain preconceived meanings of it. Then it turned into the dangers that are associated with ‘Rizq’ — the ‘Risk’ essentially.

So this is how the two terms came about; how they are coined together alludes to the dangers that we are facing every day on a global and local level.

MN: So Rizq|Risk is an umbrella term you’re using to engage with intersectional conversations around environment, sustainability, social justice and cultural heritage? What are you trying to address?

WB: I wanted it to be a balanced conversation. We talk about sustainability, but what should we do for our future that can really have this sustainability in everything. We have traditional practices, but do they really still exist? To what extent? Are they really helpful for us? Why are we not going back to tradition if they are? And: why are we looking at these green revolutions—are they useful for us? These were just some of the many questions in my mind.

But I did not want it to be focused on one thing and not the other; I did want to show just problems, but that there are solutions as well. The answers lie with women who are custodians of the lands. This brings gender into focus and how gender plays a very vital role. These women, for example, contribute immensely to the food industry. If we talk about crops, the women do all the basic work. At the end of the day, they are also victimised: they are on low wages, they are not the owners of the land. The women feel it at heart, really, that they they don’t own the land. They are working in the fields, but the one who owns them and sells the crop gets the money. Then there are health issues such as pesticides. The one who is getting money from the land is not really being in contact with all that, women are. And children, their children also get affected.

MN: So in KB24, you’re looking at both the city and farming lands and cultures. What was your community outreach approach as curator and what was the actual outreach process like?

WB: I have been involved in the not-for-profit sector for a while now. I have especially worked in villages and have been engaged with them for twenty years now. Up till now I have trained 500 women in villages all over Sindh in craft making, for example. So, I had this background already and when Anna Konik came over, I took her to the villages. There she had these very intimate conversations, emotional conversations, with women about their own existence, about their relation to their mothers and such.

She talked to them about what they remember from the way their mothers cooked and how this tradition of cooking is carried out by them. It was quite emotional. Anna is planning on bringing these women and their conversations to the Biennale.

MN: That’s wonderful. And when you say these women, these are like the village women of which area?

WB: Of Tendo Allahyar. I just want to just mention here that we also engaged the fisher folk communities in Karachi.

MN: And so, when you say ‘engage the community’, what does that mean?

WB: Fazal Rizvi, for example, will be hosting a table. A table is where we always sit and talk about everything from politics to entertainment, all around food. So that was the idea. Fazal is bringing the fisher folk community back to Karachi, who are displaced actually, and their food is not available in Karachi. So they, the custodians of Karachi, are coming back to Karachi through this table, and we are bringing them to the heart of city. They will talk about their own livelihoods, their food, their histories, their culture, and how Karachi has changed. Essentially, they are bringing an archive alive. And they are putting up the documentation and archive. This table will be activated for several times; the table itself is art.

MN: Oh, wonderful! Who are the other artists are you excited about? I’m sure you’re excited about all of them, but works which you feel especially encapsulate what this Biennale is going to be about.

WB: I’m quite excited about Lundahl and Seitl. They are a duo that works in Sweden, but they are internationally recognised for their immersive performance installations, in which they engage the audience as performers. Performing this in public allows for an engagement of a different kind—of people coming from different backgrounds and interacting with each other through their work. They will be bringing their river biographies project. This time specifically of the River Indus. It’s linked to work they have done previously. For instance, they have worked on the Thames River and a river in China.

Their project talks about the river itself, and the communities who are engaged with the river, and whose livelihood is depending on the river. But it’s also about the spirituality and history of the river itself. They talk about the sounds; they also talk about the different kind of species that exist within its waters. What is found under the water and how does the river change its course? What is the history of the river itself? A proper river biography!

So yes, then, and another artist who is coming is Tino Seghal. Sehgal is one of the names who has changed the way of looking at art in the 21st century. He’s basically a dancer. When I was looking at his practice, I was struck by how he is against the materiality. He doesn’t create any material; he’s against carbon emission and carbon production in any form. So, his work cannot be documented. His work cannot be reproduced. His work is more about emotional interaction between humans; it’s about weaving stories through interaction. His installation is created through human bodies—not material art. In his practice, he is against art which only hangs on walls or has material form. His work becomes one of the ways of talking about how we have lost this touch between the humans.

MN: Were you very conscious about bringing outliers within the purview of the art community? How did you bring in different communities into conversation with each other? Was this something that you were consciously trying to do or did it just naturally happen?

WB: It happened naturally, but it was also one of the strategies to look at such kind of projects. Really, it was something that I wanted. Different people should know each other’s problems. As I spoke about at the beginning, it was also about bringing local attention to global issues. I was focused on building connections between these global and local artists. We have artists coming in from all over, especially the Global South.

As for outliers and reaching out to a variety of people, as I said, when the conversation table will be activated, I hope that different people will come in and listen to them. There will be some taking and giving, a proper conversational exchange. There will be something which will be shared together, and there will be a togetherness as well.

I saw that there are problems in Japan for food security and there are problems in America for food security. There are problems in China too! So, these issues are not unique to just us and having these conversations about these disasters, and reflecting on how these disasters really affect communities, will hopefully create a meaningful exchange.

I have clustered different artworks in different venues, so that the audiences are able to experience a variety of ideas together, not just one aspect of food security. Very different projects are woven together, and this was done deliberately.

MN: Karachi as a city and a site. How do you think biennales shape cities and cities shape biennales?

WB: Biennales by virtue of being public art events remain within the memory of a city and its inhabitants, whatever the level of engagement of the public with the art. Then there is the material relationship between a city and biennales; often many abandoned sites are made alive for a biennale, highlighting their existence and use to people. Interventions, such as urban forest movements, that are part of biennales, are another layer of how this shaping works. I really do believe that there is a constructive relationship between biennales and public art interventions. It takes time to see the results, but they are there!

MN: Finally, what are the three words you’d use to describe the ethos of KB24?

WB: Environment, Poverty and Sustainability.

Maliha Noorani’s primary research and curatorial interest is in South Asian colonial visual culture and its intersections with modern art institutional histories. After her BFA, she read art history at SOAS and Yale. She teaches art history at The National College of Arts (Lahore) and works closely with museums as a UNESCO specialist. Her most recent projects include curating Taxila Museum’s first special exhibit, Gandhara: Routes and Roots and museum institutional development within Punjab. She is also project lead and co-curator of Crafting Histories (Glasgow Life Museums x National College of Arts).

Additionally, she was the Norma Jean Calderwood Curatorial Fellow in the Department of Islamic and Later Indian Art at the Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Harvard Art Museums. She has worked at institutions such as Sotheby’s London and the Asia Art Archive in Hong Kong. Through her work in cultural and educational institutions, Noorani’s research engages with themes around decolonising art histories, intercultural encounters, patronage and artistic production, the circulation and consumption of visual and material culture. Presently, her favourite course to teach is Global Modernism: Outliers and Art Histories.

Comments